My name is Ziya Tian, I am a junior studying biology and computer science, and I am thrilled to receive the IDEA Grant this year. Over the summer, I will be developing a computational tool that reconstructs the evolutionary history of cancer cells.

One of the most fascinating and terrifying aspects of cancer is its ability to mutate, leveraging the same principles of evolution that govern all living things to invade the body. As the disease develops, new cancer cells inherit the mutations from their parent cells and may gain new mutations that confer different characteristics, branching into distinct clusters of cells called clones. This process leads to the presence of multiple clones in the same tumor simultaneously, which complicates cancer treatment, as different clones may require different treatment strategies. Small clones that are missed during initial treatment may also cause a relapse of cancer. Thus, understanding the evolutionary history of cancer is crucial to designing effective cancer treatment.

When a patient is diagnosed with cancer, often the disease has already grown to the point where multiple clones exist, and unfortunately, we cannot look back in time to trace how the mutations progressed. However, with the power of statistics and computer science, we can infer how the mutations occurred based on how frequently each mutation appears in a current cancer sample from the patient. Of course, this is a simplified description, and the actual implementation is a bit more complex. In particular, there are two complications that I plan to address with my computational tool.

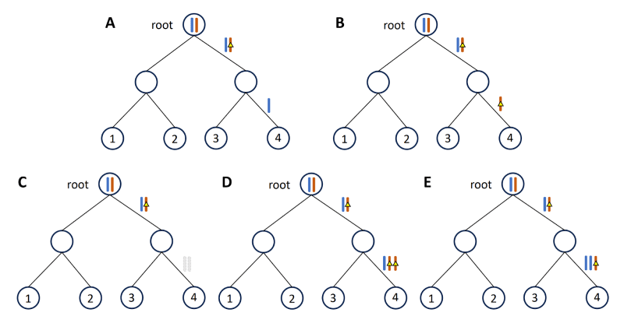

First of all, cancers can contain different types of mutations that vary widely in size, from single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) that alter one base of the DNA sequence, to copy number aberrations (CNAs) that alter large segments of chromosomes. Most existing computational tools focus on either SNVs or CNAs, and the interplay between SNVs and CNAs is not well understood. I plan to consider both types of mutation in my tool, which means that I have to account for all cases of overlapping SNVs and CNAs, since any subsequent amplification or deletion of the CNAs would cause the SNVs to be multiplied or lost accordingly. Furthermore, an SNV can overlap with multiple CNAs, and each CNA can be gained or lost multiple times, which adds more complexity to the project.

Secondly, not only are there different types of mutations, but also different types of sequencing technologies by which the mutations are detected. Traditionally, all cells in the sample are pooled together to be sequenced in bulk, but more recent developments in single-cell DNA sequencing technology (scDNA-seq) has enabled each cell to be sequenced individually, which greatly facilitates the reconstruction of the phylogenetic tree. However, scDNA-seq can detect either SNVs or CNAs at high sensitivity but not both simultaneously, so identifying both SNVs and CNAs from the same tumor requires sequencing the cells in two batches, which may result in sampling bias that must be addressed. In addition, performing scDNA-seq on two sets of cells is expensive, especially for SNV detection, as each cell must be sequenced at a high coverage. Therefore, my project aims to use scDNA-seq to detect CNAs and higher-coverage bulk sequencing to detect SNVs, sacrificing their single-cell resolution.

In the summer, I will start by designing the statistical models and algorithms in my program with the guidance of Dr. Xian Mallory and spending lots of time coding them into reality. Once that is complete, I will work on generating simulation data to test my program and validate the output. This project is a great opportunity for me to familiarize myself with applying statistics and programming to biological problems as I plan to pursue a Ph.D. in bioinformatics/computational biology after college. I sincerely hope that the results of my research will contribute to the broader efforts in understanding of how cancer cells emerge, evolve, and metastasize, and my computational tool can aid other researchers in analyzing their sequencing data to develop treatments for cancer.

Wow! This is wildly complex and I know nothing about it, but you explained it so clearly. I’m very interested in this topic now and I will try to learn more about it.

LikeLike