The rehearsal process was where I found the most challenges in this project. The concept, logistics, working with designers, and even running the show itself had their unique hurdles, but rehearsal was the largest part where I was continuously navigating different obstacles. As I mentioned in a previous post, this project operates within a more conventional production schedule and format. We are staging a text with four weeks of rehearsals and about a month or two of pre-production work leading up to rehearsals. This lies in stark contrast to the work I did previously in Honors in the Major, where a whole semester was taken to devise a performance piece from scratch.

Time was not devoted to sitting and writing a play, but rather we improvised and experimented as actors for a long period of time. We then edited a performance piece together from that material. This process centers the actor as a primary creative agent in the performance. In the conventional method, the actor is often an executor of a third party’s creative vision (the director or the writer). I did not want to work that way, so I collaborated with Kris Salata, my mentor, on alternative ways of working. Thinking more on it I realized that the only hard limitation I had was the timeframe, which doesn’t mean I have to follow that traditional production method. So, I chose to use active analysis through my rehearsals to engage the actor more fully in the work.

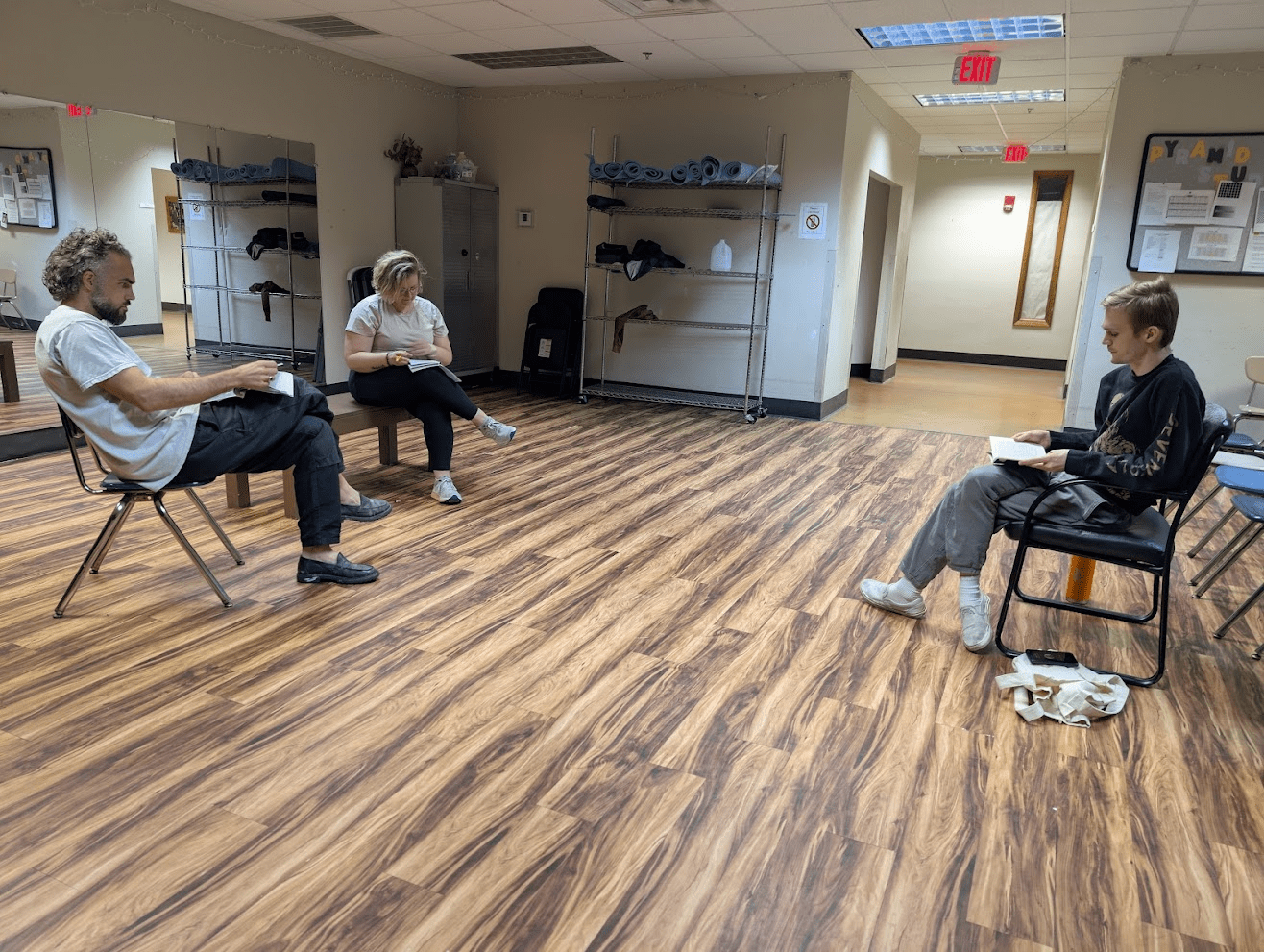

Active analysis was a concept developed by the Moscow Art Theatre and Stanislavski in the later part of his lifetime, and in reality, is one step in a long line of deep experimentation with performance to which a multitude of people have contributed. It replaces a more traditional textual analysis of the play, which the director and actors might do separately on their own time. Instead of simply reading the play as if it were literature, it is analyzed through staging it and playing with it. This was the first major hurdle; not only was I trying a new and difficult technique for the first time, but I was also working to teach it to my actors who had no previous experience with active analysis. I would walk them through an improvisation based on a scene and ask them, “How did that feel?”.

At first, it was clear they didn’t know what I meant by this. It forced me to be more specific in how I worked with them and be very particular in my wording. I was worried about giving them my opinion or viewpoint too early; I didn’t want my actors to latch onto my view as the correct way of doing things before they investigated their perception. This was a large adjustment period, but over time me the actors and I developed a language with each other that allowed us to dig into a scene as peers, rather than a director who holds all the answers, and the actor who must execute them. We would still mix this with “table work”, where we sit down and read a section, then discuss it. There would be days were we thought we had a scene figured out, but once it was on its feet, it felt… wrong, or hollow. After a couple of hours, one question, one discovery would unlock a new understanding of the play, which we could have never achieved without collaboration. This was an immensely rewarding moment of which there were many.