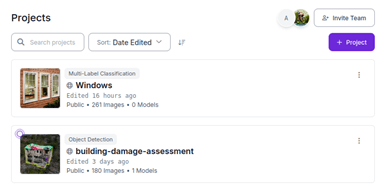

This month has been an eventful one for us. We already have a basic model that can detect damaged windows reasonably well; however, this alone isn’t sufficient to achieve our broader goal of drone-based damage assessment. To move closer to that goal, we decided to revisit the dataset used to train the original model and expand the labeling to include other types of damage. For this task, we chose to use Roboflow—a decision that would soon lead to our first major complication.

The initial challenge was that the dataset was simply too large for Amber and me to label on our own. Even after dividing the roughly 200-image dataset between us, the process proved to be extremely time-consuming. What made it worse was how unengaging the work felt. As a result, we decided to pause the labeling and train a new model with what we had labeled so far.

At that point, we ran into another issue: Roboflow wouldn’t allow us to add the newly labeled images to the dataset. This became a major roadblock. I spent several days trying different solutions, including deleting all unlabeled images from the dataset, but nothing worked. Ultimately, the fix came from reaching out on the Roboflow forums and asking the support team to handle it directly. Up until then, I had only ever browsed forums for help—but this experience made me more willing to post questions when I need answers.

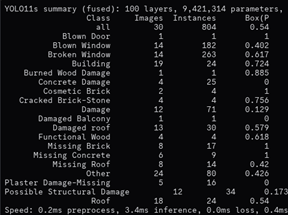

Once that was resolved, we were finally able to train our new model. Unfortunately, the results were disappointing—it only performed correctly about 40% of the time. We realized that continuing to label or relabel the dataset in hopes of marginal improvements wasn’t the most effective path forward. Instead, it made more sense to pivot and try a different approach altogether.

We believe a more efficient path is to focus on one aspect of a building at a time. For now, that means perfecting our model for assessing the cost of broken windows before expanding to other types of damage. To keep with the windows example, we will create a pipeline where specific details about the window will be able to be classified, the type of window, the type of damage to be able to better estimate the cost of window repair.

The second issue we faced was with the drone itself. It turned out the one we were planning to use wasn’t compatible with the DJI Android API, leading us to scour the depths of eBay for an alternative. Thankfully, we had enough grant money to purchase a new drone—but that wasn’t the end of our drone-related problems.

It turns out that, for testing, one of us will need a drone license. To get the license, we will have to study for the FAA Small Unmanned Aircraft exam. This will be the first exam of its kind that I’ve taken, and I can’t say I’m not a little concerned—an 88-page study guide filled with links to legal statutes is certainly daunting.

On the bright side, one of our colleagues, Sumanth (who worked on the original drone damage assessment project), is on the verge of a breakthrough with his synthetic data research. He’s offered to give us full rights to use his work, which would save us a lot of time otherwise spent scraping the internet for medium-at-best images.

To end things off, despite our setbacks, I’m now feeling optimistic about the project. We finally have a clear direction for how we are going to accomplish our goals. These two months have been great in the opportunity they have presented to me; the chance to work on an ambitious project without having to worry much on the repercussions of failure. Throughout these weeks, my leadership skills and my development skills have improved because of constant communication with my team. I am sure we will be able to create something beautiful in October!