In prison there is a saying, “From the dirt I will rise.” It’s a quiet promise, a seed planted in soil others thought barren. Every research journey is a path of discovery. Mine began as a subject–Degrees of Opportunity: Mapping Success and Barriers for Justice-Impacted Students. But over the summer, it led to an educational and meaningful trip to Washington, DC, the National Archives, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and Georgetown University’s Prison Scholars Program, which is part of their Prisons and Justice Initiative (PJI).

Strong emotions flowed as I stood in Abraham Lincoln’s shadow, the architect of the Emancipation Proclamation. From this experience I’ve found that even before the first research interview is conducted, the learning has already begun. I’ve also been immersed in the formative stages of research, namely preparing the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application so I can get approved to interview and work with human subjects. This is an opportunity to root my research in compassion, clarity, and care. Whether it has been designing the recruitment flyer, crafting the informed consent agreement, or finalizing protocols for surveys and interviews, the IRB process has taught me that every detail must affirm dignity and reduce harm. For example, none of my research materials use stigmatizing language, such as ex-felon, ex-inmate, ex-convict, or ex-offender. This process has helped me grow not only as a researcher, but as a person committed to trauma-informed and justice-centered inquiry.

This summer also gave me the opportunity to learn directly from institutions leading the way in prison education. At the DC Jail, Georgetown University offers for-credit college courses taught by its own faculty. This is not charity. It is a rigorous, intellectually empowering academic program that affirms the humanity and potential of incarcerated students.

I was deeply moved by how Georgetown centers justice-impacted learners in its mission. Alumni of the program are now pursuing bachelor’s degrees and leading change beyond prison walls. Tyrone Walker is a perfect example. After studying in his jail cell, he became the first student in the program to graduate from Georgetown, earning a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies. Today, as PJI’s Director of Reentry Services, he supports others coming home. PJI’s executive director Marc Howard says of Tyrone: “He has proven that people can overcome their worst mistakes,” emphasizing that with education, professional training and compassion, “incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people can achieve tremendous success.” Having met Tyrone in person, it reminded me of what is possible when higher education does more than offer access; it builds pathways from prison to university, and from trial to transformation.

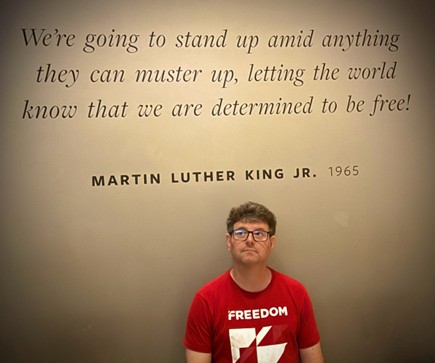

At the Lincoln Memorial I wore my “FREE TO SERVE” shirt, a personal declaration of survival and service. At the National Archives, where the Constitution and Bill of Rights are housed, I wore my “EXTRAORDINARY (Not Ex-Felon)” shirt, a quiet protest against the stigmas that follow people with records. But the moment that moved me most came at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where I learned about Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore.

The Moores were Black school teachers in Brevard County, Florida who became fighters for educational freedom, and ultimately the first martyrs of the modern civil rights movement. Through the NAACP, they organized for equal pay for Black teachers, registered tens of thousands of Black voters, and challenged systemic injustice during Jim Crow. On Christmas night, 1951, a bomb beneath their home took their lives. Their story was later honored by Langston Hughes in The Ballad of Harry T. Moore, a poem set to music by the African-American a cappella ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock. Before the music begins, Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon delivers a powerful preamble: “He was so good, they had to kill him.” And then, this refrain:

No bomb can kill the dreams I hold,

For freedom never dies.

As a justice-impacted individual who spent 31 years, 2 months, and 8 days in 17 maximum-security prisons this legacy is personal. Today, I’m a public policy student at Florida State University with a 4.0 GPA, a Jack Kent Cooke Scholar, and a newlywed. The Moores’ work centered on education, voting rights, and equal access, which are issues still being fought and won today. Their lives were taken for expanding opportunity; our lives today are shaped by how we protect and grow that legacy. Every act of justice, whether in a classroom, courtroom, or research study, is a step in the long march toward freedom. Their story gave my work context and my spirit courage.

For Freedom never dies!

As soon as I returned to Tallahassee, I paused to reflect; not just on my journey to the nation’s capital, but on the ground I walk every day here at Florida State University. Near the Oglesby Union, in Woodward Plaza, stands a bronze testament to educational access and courageous firsts: the Integration Statue. It honors three of the first African American students to integrate FSU: Maxwell Courtney, the university’s first Black graduate; Fred Flowers, the first Black athlete; and Doby Flowers, the first Black Homecoming Princess. The trio stand in quiet but powerful identity rooted in the struggle to ensure Black students have access to education. Like those who were once denied access to education based on their skin color, justice-impacted students are contributing to this institution simply by being here. We are part of a new chapter in the ongoing story of opening doors.

I see the work we are doing at FSU as part of a growing national movement. Degrees of Opportunity will show and highlight the power of faculty engagement, peer mentorship, and university commitment to creating educational spaces that recognize potential. But it will also show us where work still needs to be addressed to erase stigmatizing labels. My DC trip affirmed that what we are building at Florida State is timely, relevant, and rooted in a broader vision of justice through education.

For Freedom never dies!

What is next? With IRB submission prepared and instruments finalized, I’m ready to begin recruitment and data collection in the coming weeks. To help with this monumental endeavor we are creating FSU’s first ever Justice-Impacted Student Organization (JISO) which, once approved, will establish a Registered Student Organization, or RSO, fully dedicated to advancing the civil rights and responsibilities of students who have been impacted by the criminal legal system, either directly or through a loved one. It will serve as a hub for this research and a space for advocacy beyond the study itself. With gratitude, I have met some amazing students and thought leaders who have already begun mapping out how to visually document this project through photography, presentations, and messaging that reflects the brilliance and resilience of justice-impacted students. Community support for this project is what freedom-building looks like. This is what opportunity creates. And any FSU student can join and be part of JISO.

As I look ahead to conducting interviews, focus groups, and analysis, I know there will be more lessons. But I also know the roots are deep and the vision is clear. The biggest hurdle now is time and making sure every phase is done with care. But I’ve built flexibility into the schedule and grounded this project in relationships and readiness.

If this summer has taught me anything, it’s this: research is never just academic. It’s personal. It’s spiritual. It inspires change. It is about creating space where no one is boxed out of opportunity, especially those who have already fought hard just to be here. From the dirt, we rise–not just as scholars, but as a community determined to be seen, heard, and never again erased.

Ex-Felon

Ex-Inmate

Ex-Convict

Ex-Offender

Extraordinary!