Hi there! My name is Brooke Taylor Hagans, and I’m an undergraduate researcher studying Biological Science at Florida State University. This summer, I’m incredibly grateful to be conducting independent research through the FSU IDEA Grant, a program that supports original, student-led projects. With this support, I’ll be exploring a question that connects physiology, parasitology, and marine conservation:

“How do parasites affect stress in pregnant stingrays?”

It’s a question rooted in both curiosity and conservation. I’ve always been drawn to the invisible hurdles animals face, especially during major life stages like reproduction. Pregnancy is already one of the most energetically demanding periods in an animal’s life. But what happens when you add parasites into the mix? That’s the mystery I’ll be diving into.

I’ll be conducting this research at the Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory (FSUCML), where I’ve spent the past year working with rays under the mentorship of Ph.D. candidate Annais Muschett-Bonilla and Dr. Dean Grubbs. Through their guidance, I’ve come to appreciate how subtle stressors—like parasitic infections—can influence the health, behavior, and reproductive success of marine animals in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Atlantic stingrays (Hypanus sabinus), the focus of my study, are small coastal elasmobranchs found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern U.S. Unlike many fish, they give birth to live young through a reproductive process called matrotrophy, where mothers provide nutrients directly to their embryos throughout development. While this strategy benefits their offspring, it comes at a steep physiological cost for the mother. Just like in other vertebrates, immune function in stingrays can become suppressed during pregnancy, potentially leaving them more vulnerable to parasites.

To make matters more urgent, climate change is likely intensifying the problem. Rising ocean temperatures and changing salinity levels can boost parasite survival, reproduction, and transmission rates. For pregnant stingrays already managing the demands of matrotrophy, this added pressure could have serious consequences. By understanding how parasitism and physiological stress interact during reproduction, we can begin to build better care protocols for rays in both wild and captive settings, something that’s especially vital for conservation in a changing climate.

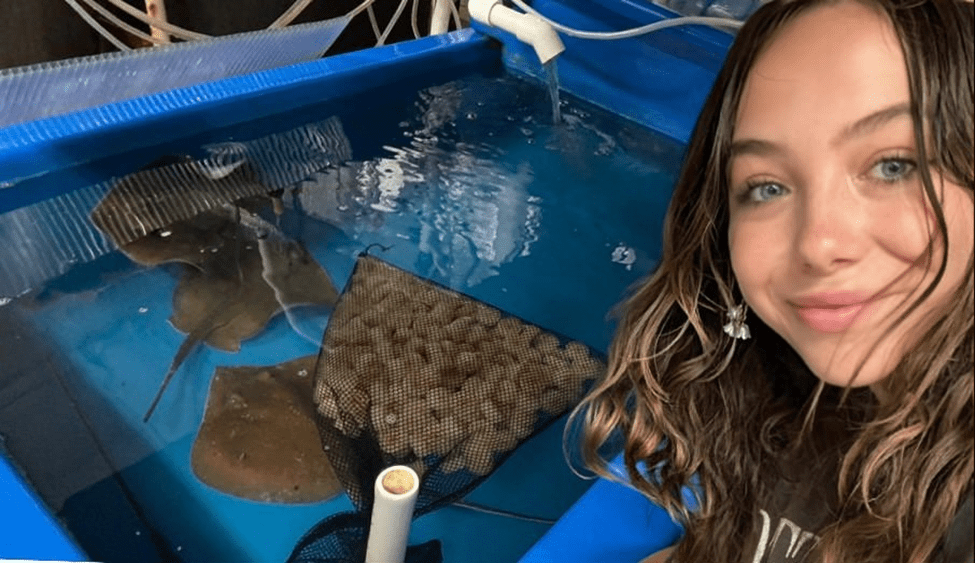

Each month from May to August, I’ll help collect five mature female stingrays from the shoreline near FSUCML using seine nets. After capture, they’ll be housed for one week in flow-through seawater tanks. During that time, I’ll monitor their health, collect blood samples to assess hematocrit and lactate (key indicators of physiological stress), and perform skin swabs to evaluate external parasite loads. I’ll also inspect the mouth and spiracles to document internal parasites. After a week, each ray will be released back into its original habitat.

In the lab, I’ll use ImageJ software to quantify and characterize parasites from my samples. Then I’ll examine whether increased parasite loads are linked to higher stress levels, and whether both increase as pregnancy progresses. I predict that rays with heavier parasite burdens—especially in later stages of gestation—will show elevated stress biomarker concentrations. If that holds true, it could offer new insights into how reproduction, immunity, and environmental pressures collide.

This project isn’t just a line on my résumé, it’s a reflection of what I love. I’ve always been captivated by the unanswered questions in animal behavior, the hidden rules of social networks, the formation of lifelong bonds, the signs of intelligence we’re only beginning to recognize. I want to spend my life chasing those questions. After graduation, I plan to pursue a Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolution, with a focus on the evolution of sociality, cognition, and cooperation in animals. Whether I’m studying stingrays, birds, or other species, I’m drawn to the mystery of how animals connect, communicate, and survive together. I can’t imagine doing anything else. My dream is to become a professor and researcher, not just to make discoveries, but to mentor others who feel the same pull toward understanding the natural world—its beauty, its complexity, and its brilliance.

I’m deeply thankful to the Center for Undergraduate Research and Academic Engagement for funding this project through the IDEA Grant, and to Dr. Dean Grubbs and Annais Muschett-Bonilla for their extraordinary mentorship and support. I’m also grateful to my family and friends for cheering me on every step of the way.

This summer, I hope to contribute something meaningful to the field of marine biology—and to take one more step toward a future dedicated to research, conservation, and education.