Hello reader!

I hope you have been having a restful summer and mentally preparing for the next school year to start.

I can’t believe it’s August already and the summer is over. It’s my last summer as an undergraduate. It feels very bittersweet. As excited as I am to (hopefully) start graduate school next year, I will miss the community I’ve built and settled into here at FSU.

I’m struggling to put into words how excited I am to share my research experience and progress at the President’s Showcase this October! More than anything, I’m excited to share my passion and appreciation for experimental physics with whoever comes to my poster. I love presenting my research. Isn’t the whole point of doing research to share it?

I’ve learned that performing a single experiment takes a lot of planning, infrastructure, funding, and collaboration in nuclear physics. There are ~3500 known unique radioisotopes. Different laboratories, like FSU’s Fox Laboratory, choose to conduct many different experiments with varied detection instruments, and each experiment has many different reaction “channels”, or probabilities. Think of how many different reactions are possible to plan and execute!

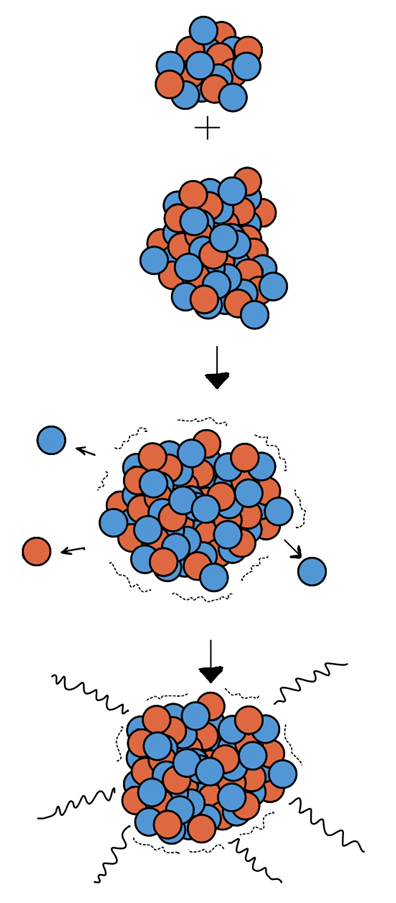

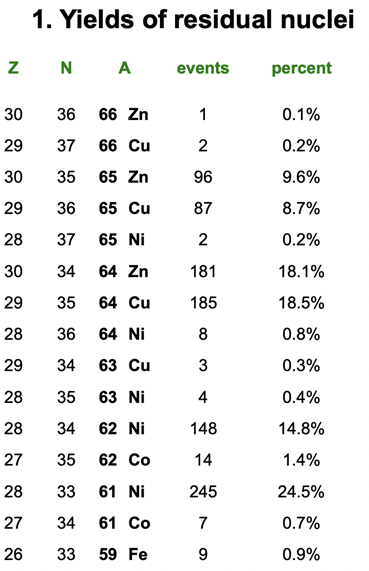

Lets take a look at the reaction I studied this summer as an example. A 55 Mega electronvolt beam of charged oxygen-18 interacts with a solid titanium-50 target and undergoes a fusion evaporation reaction (Figure 1). A fusion evaporation reaction first involves the formation of a compound nucleus as the target and beam fuse together. For this reaction , the compound nucleus is zinc-68. The excited system then radiates protons and neutrons and produces a spectrum of daughter nuclei with varied probabilities (Figure 2).

50Ti(18O E=55 MeV, fusion evaporation).

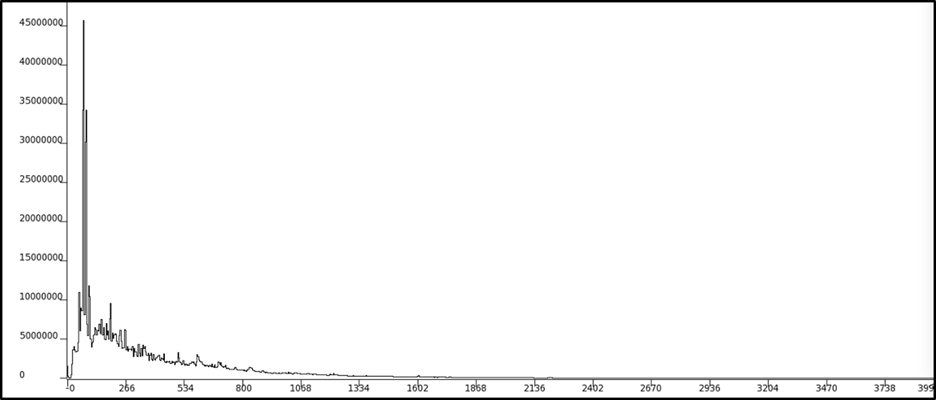

This experiment was conducted last year with focus on the nucleus nickel-61, but this data still produced a significant amount of other nuclei that have a lot of missing information in evaluated nuclear data libraries: one of them being copper-65! Surrounding the reaction site were 9 total gamma ray detectors placed at varied angles. Only a fraction of the gamma rays end up depositing their energy into these detectors (germanium crystals), which is converted into an electronic signal, and then converted into a spectrum of counts vs. energy that I can see on the computer (Figure 3).

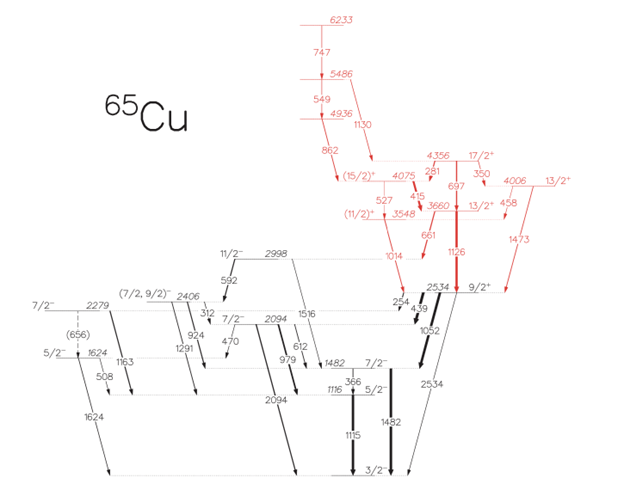

The shape of these peaks and how their intensities varied at the different angle placements can provide information on the nuclear structure (i.e. level scheme) of copper-65. Here’s a paper with one of the most recent level schemes of copper-65 (Figure 4). Basically, the goal is to discover more lines and place them correctly on the level scheme! Ok, I’ll stop now, but I’m excited to (hopefully be able to) explain the physics behind this level scheme to whoever decides to come to the President’s Showcase!