By Maya Parfitt, William & Mary

So far, all the archaeological projects I’ve been a part of have led me to the most charming places. Maybe it’s the fact that I’ve only worked in the Balkans, where stuff sometimes feels chaotic or upside down to outsiders. As soon as I stepped foot on Naxos, after flying on one of the smallest planes I’ve ever been on, I was greeted by an equally small airport. For some reason, seeing the tiny building put me at ease – I took it as a sign that my trip would be a good one.

Left: My new favorite airport. Right: Photo from a visit to one of Naxos’ beautiful beaches!

The idea of spending ten days on a Cycladic island with a group of international scholars and students was both exciting and scary to me, especially after I realized I’d technically be the youngest member of the team. But when something sparks a little bit of fear, I think there’s reason to move toward it. The night I arrived on Naxos, I was introduced to almost all the team members I hadn’t met at a gyro-filled dinner table by the sea. The next day was when our work started.

This season, the goal of the Naxos Quarry Project (NQP) was to holistically investigate an ancient marble architectural block in the island’s Melanes Quarry, abandoned in antiquity. This block is colossal – about twenty-four feet long – and what archaeologists would call a “monolith”, since it’s large and carved from a single piece of stone. We aimed to figure out where in the quarry the block was extracted from, why it was abandoned, and its intended function. My independent research focus was on the ancient workers that produced it – how they did their jobs, what their lives were like – since there’s barely any mention of them in the historical record despite their inseparability from ancient Greek marble production.

My hope was that by retracing the origins of the monolith with the NQP, I could also gain insight into the workers who made its existence possible.

Left: The “Portara” at sunset. Right: The NQP team documenting the temple.

No other scholars have done a full-scale study of the monolith, but it has been mentioned in some earlier publications because of its potential relationship to Naxos’ most famous landmark: the unfinished “Portara” temple on Palatia islet. The temple’s most notable feature is an enormous marble doorway that’s been standing since it was first built, over 2,500 years ago. Right before the entire team got to Naxos, we got permission to survey the temple ruins, an incredibly pleasant surprise! And this is where I learned my first lesson: the importance of local communities in archaeological work, a common theme throughout my trip to Greece. We were lucky to have a Naxian and Ephoreia representative on site – Vasiliki Anevlavi, a specialist in ancient marble – who described just how important the “Portara” is to Naxian identity. She put it this way: if it falls, so does Naxos. Archaeology is about all kinds of relationships. The goal might be to connect artifacts to as much of their past context as possible, but now I believe it’s just as important to consider their present one, too. It can change the way that projects are structured and emphasize the importance of being a steward of heritage.

The first time I went to the Melanes Quarry with the other students, I learned about something incredibly useful to my research, a place identified as “The Sanctuary of the Source”, excavated by the University of Athens in the early 2000s. It was so exciting to me because it seemed to be a site by quarry workers, for quarry workers…or at least one that was frequented by them! Scholars suggest that it was a religious area, dedicated to the gods Otos and Ephialtes, who were mythical twins associated with moving mountains and rock (it makes a lot of sense that the people who worked with stone – a very dangerous job – chose these figures as their patrons and protectors). But what was peculiar to me was that there were also unexpected and more domestic elements to the site, like terracotta pots embedded in rock walls for beekeeping. Also found at the “Sanctuary of the Source” were marble offerings to the gods, on display at the small Melanes Museum. They’re smaller scale, and vary in completeness. One of my favorites is an unfinished Sphinx, which shows distinct tool marks.

Speaking of tool marks, a skill that I learned from the senior members of the NQP was how to identify ancient tooling – imprints left behind by the workers I’m investigating – which give great insight into their techniques and equipment. If a person with no prior knowledge stood in the Melanes Quarry, they probably wouldn’t differentiate it from the rest of the Naxian countryside. This is a large problem with documenting ancient quarries to begin with – they can be difficult to spot. That’s part of why the NQP used digital field methods like LiDAR and photogrammetry in tandem with more traditional ones. Once I became familiar with the different types of toolmarks, though, they were all I could see. It was like a scavenger hunt with the team, and it was extraordinary to realize just how much hides in plain sight.

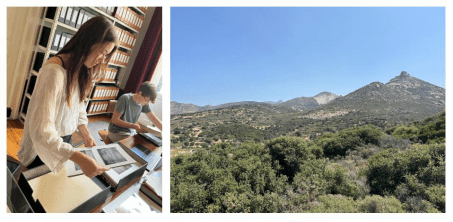

Left: Archival work at the German Archaeological Institute in Athens. Right: View from Melanes. The light colored mountain in the middle is actually a modern marble quarry!

On Naxos, I had the chance to encounter beautiful, incredible things: an abandoned statue over thirty-feet tall, a small Byzantine church that incorporated the ruins of Roman baths into its construction, a mysterious ancient inscription on the face of a cliff in the Apollonas Quarry. But there was one thing I came into contact with that was difficult to conceive of, and it wasn’t ancient…it was Adobe Illustrator. In the field, you’re constantly taking measurements and sketching by hand, but when it comes to creating publications, using a digital medium makes it easier to create accurate and easily shareable archaeological drawings. Along with two amazing master’s students from King’s College – Nana Smith and Jemima Jayne – I learned how to use the software. It was definitely humbling, with hours spent at our usual cafe-workspot in Chora under the guidance of Professor Rebecca Levitan, an expert in ancient Mediterranean sculpture. But everyone starts from somewhere, and with Adobe Illustrator, even seasoned archaeologists have trouble. Soon I began to enjoy the process, I started to feel more comfortable with it. By the time I got to Athens, I helped to make a scaled drawing of the monolith, one that would get submitted to the Ephoreia in a report.

Now that I’m back in the States, I’ve been sorting through all of the evidence I’ve collected from my time in Greece for my culminating project. I feel so lucky to have been a part of the NQP, and grateful that the Tyler Center has given me this opportunity to explore my interest up close. Having seen the monumental work of ancient Naxian quarriers in person, I feel a greater responsibility to share their importance with an everyday audience. I’m excited to see where I can take it.